The Ultimate Guide to Understanding British Insults

The British have turned the art of the insult into a cultural institution. From cutting sarcasm to elaborate put-downs, British insults range from the mild and affectionate to the genuinely offensive. Understanding this complex vocabulary is essential for anyone hoping to navigate British culture, whether you’re watching British television, reading British literature, or simply trying to understand if your British friend just complimented or insulted you.

This comprehensive guide explores the rich and varied world of British insults, explaining not just what they mean, but how, when, and why they’re used. Because in Britain, context is everything, and the same word can be either devastating or endearing depending on tone, relationship, and situation.

The British Approach to Insults: Cultural Context

Before diving into specific terms, it’s important to understand how British insult culture differs from American:

Affectionate Insults Are Common British friends frequently insult each other as a sign of affection and camaraderie. “You absolute wanker” between mates is friendly banter. The same phrase to a stranger is genuinely hostile. Americans often find this confusing.

Understatement and Irony The British excel at devastating insults delivered with impeccable politeness. “How interesting” can be the ultimate put-down. “Bless your heart” has nothing on British passive-aggression.

Class Consciousness Many British insults reference social class, education, and sophistication (or lack thereof). These class-based insults carry weight in ways Americans might not immediately grasp.

Regional Pride Insults often target regional stereotypes—Northerners call Southerners soft, Southerners call Northerners uncouth, everyone has opinions about the Scots, Welsh, and Irish.

Swearing Is Different British swearing follows different rules than American swearing. Some words considered extremely offensive in America are casual in Britain, and vice versa.

The Severity Scale: From Mild to Nuclear

British insults exist on a spectrum from playful teasing to genuinely offensive. Here’s how to gauge severity:

Tier 1: Mild/Playful (Generally Acceptable Among Friends)

Silly/Daft Meaning: Foolish or not thinking clearly Usage: “Don’t be daft” or “You silly sod” Context: Very mild, often affectionate

Muppet Meaning: Idiot, fool (from the Muppets TV show) Usage: “You complete muppet” Context: Playful, rarely genuinely offensive

Wally Meaning: Fool, idiot Usage: “What a wally” Context: Old-fashioned, quite mild

Pillock Meaning: Stupid person, idiot Usage: “You pillock!” Context: Stronger than “silly” but still relatively mild

Numpty Meaning: Idiot, fool (Scottish origin) Usage: “He’s a right numpty” Context: Affectionate to mildly insulting

Plonker Meaning: Idiot, fool (made famous by “Only Fools and Horses”) Usage: “You plonker!” Context: Usually playful, rarely serious

Doughnut Meaning: Idiot, fool Usage: “You absolute doughnut” Context: Very mild, often humorous

Div Meaning: Idiot, stupid person Usage: “What a div” Context: Mild, common among younger people

Tier 2: Moderate Insults (Depends Heavily on Context)

Tosser Meaning: Literally someone who masturbates, but used to mean jerk or idiot Usage: “He’s such a tosser” Context: Moderately offensive, common in casual speech

Wanker Meaning: Literally someone who masturbates, means idiot or contemptible person Usage: “You wanker” or “What a wanker” Context: Can be friendly between mates or genuinely insulting to others Note: Much more casual in Britain than “jerk off” would be in America

Knob/Nob Meaning: Penis, but used to mean idiot or unpleasant person Usage: “He’s a complete knob” Context: Moderately vulgar, quite common

Bell-end Meaning: Glans of penis, used to mean idiot or contemptible person Usage: “You bell-end” Context: Vulgar but very common, especially among younger Brits

Prick Meaning: Penis, but means unpleasant or contemptible person Usage: “Don’t be such a prick” Context: Fairly harsh, definitely insulting

Git Meaning: Unpleasant, foolish, or contemptible person Usage: “You miserable git” or “Silly git” Context: Quite British, can be affectionate or genuine insult

Berk Meaning: Fool, idiot (from Cockney rhyming slang “Berkeley Hunt”) Usage: “You berk” Context: Sounds mild but has vulgar origins most people don’t know

Minger/Munter Meaning: Ugly person Usage: “She’s a minger” Context: Mean-spirited, insulting appearance

Chav Meaning: Working-class person with particular fashion/cultural markers, considered trashy Usage: “He’s such a chav” Context: Classist, derogatory, quite offensive

Scrubber Meaning: Promiscuous woman, low-class woman Usage: “She’s a scrubber” Context: Sexist, derogatory, old-fashioned but still used

Slag Meaning: Promiscuous person, usually woman Usage: “She’s a slag” Context: Quite harsh, gendered insult

Slapper Meaning: Promiscuous woman Usage: “Dressed like a slapper” Context: Sexist, derogatory

Tart Meaning: Promiscuous woman Usage: “She’s a right tart” Context: Derogatory but somewhat old-fashioned

Scrote Meaning: Worthless person (from scrotum) Usage: “Little scrote” Context: Crude, dismissive

Gobshite Meaning: Idiot who talks nonsense (Irish origin but used in Britain) Usage: “He’s a gobshite” Context: More offensive than simple “idiot”

Tier 3: Strong Insults (Genuinely Offensive in Most Contexts)

Bastard Meaning: Unpleasant person, difficult person Usage: “He’s a right bastard” Context: Can be affectionate between friends (“You lucky bastard”) or genuinely insulting Note: Not about illegitimate birth in modern usage

Arsehole/Asshole Meaning: Very unpleasant, contemptible person Usage: “Complete arsehole” Context: Definitely insulting, quite harsh

Twat Meaning: Vagina, but means idiot or contemptible person Usage: “What a twat” Context: Quite offensive, vulgar

Cock Meaning: Penis, means idiot or unpleasant person Usage: “He’s a cock” Context: Definitely insulting

Dickhead Meaning: Stupid or contemptible person Usage: “You dickhead” Context: Harsh, definitely insulting

Wazzock Meaning: Stupid or annoying person (Northern English) Usage: “You wazzock” Context: Sounds funny but genuinely insulting

Bawbag Meaning: Scrotum, means contemptible person (Scottish) Usage: “Ya bawbag” Context: Vulgar, Scottish specialty

Fuckwit Meaning: Extremely stupid person Usage: “Absolute fuckwit” Context: Very harsh

Prat Meaning: Incompetent or stupid person Usage: “You prat” Context: Fairly strong insult

Muppet/Absolute Muppet Meaning: When “absolute” is added, it becomes more insulting Usage: “You absolute muppet” Context: The intensifier changes the severity

Bellend Meaning: Idiot, fool (anatomical reference) Usage: “Complete bellend” Context: Crude, commonly used

Tosspot Meaning: Idiot, useless person Usage: “He’s a tosspot” Context: Old-fashioned but insulting

Tier 4: Nuclear Options (Extremely Offensive)

Cunt Meaning: The most offensive word in British English when used as insult Usage: “He’s a cunt” Context: Extremely offensive, but paradoxically can be affectionate among close Australian/British friends in some circles Note: Much more offensive in Britain than in Australia; in America it’s considered one of the worst words

Fuck off Meaning: Go away, expressing strong rejection Usage: “Fuck off!” or “Fuck right off” Context: Very aggressive, ending conversations

Piss off Meaning: Go away, leave me alone Usage: “Piss off!” or “Oh piss off” Context: Definitely rude but less severe than “fuck off”

Bugger off Meaning: Go away Usage: “Bugger off” Context: Still rude but milder than the above

Category-Specific Insults

Intelligence-Based Insults

British culture has numerous ways to call someone stupid:

Thick “Thick as two short planks” – Very stupid “Thick as mince” – Extremely stupid (Scottish) “A bit thick” – Not very bright

Dim “Dim-witted” – Stupid “He’s a bit dim” – Not intelligent

Simple “He’s simple” – Lacking intelligence or sophistication

Not the sharpest tool in the shed British version of American sayings about intelligence

Hasn’t got both oars in the water Missing something mentally

Lights are on but nobody’s home Appears functional but lacks intelligence

Couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery Completely incompetent (a piss-up is a drinking session)

Daft as a brush Very silly or stupid

Soft in the head Not thinking clearly, foolish

Barmy/Barking/Barking mad Crazy, insane

Mental Crazy (can be affectionate: “You’re mental, you are”)

Mad as a box of frogs Completely crazy

Lost the plot Gone crazy, lost sense of reality

Away with the fairies Not paying attention, in a dream world

Not all there Lacking intelligence or sanity

Appearance-Based Insults

Minger/Munter Ugly person

Munter Very unattractive person

Rough Unattractive, unwell-looking “She looks rough”

Rough as a badger’s arse Extremely unattractive or hungover

Face like a bulldog chewing a wasp Very ugly or unpleasant expression

Face like a slapped arse Miserable or unattractive expression

Butter face “Everything looks good but her face”

Built like a brick shithouse Heavily built (can be insult or compliment depending on context)

Gormless Stupid-looking, vacant expression

Grotty Unpleasant looking, dirty, unattractive

Manky Dirty, disgusting, poor quality

Mingin’ Disgusting, unattractive (Scottish/Northern)

Boggin’ Disgusting, revolting (Northern)

Character-Based Insults

Jobsworth Someone who follows rules inflexibly and officiously “He’s a right jobsworth” Origin: “It’s more than my job’s worth”

Busybody Someone who interferes in others’ affairs

Nosy parker Overly curious about others’ business

Curtain twitcher Nosy neighbor who watches others

Grass Informer, snitch, someone who tells on others

Snitch Informer (more American but used in Britain)

Nark Police informer or annoying person

Snide Deceptive, underhanded, or fake

Sly Sneaky, untrustworthy

Two-faced Hypocritical, saying different things to different people

Snake Untrustworthy, backstabbing person

Slippery Untrustworthy, evasive

Wet Weak, feeble, lacking backbone “Don’t be wet”

Soft Weak, easily manipulated “You’re too soft”

Wimp Weak, cowardly person

Jessie Weak, effeminate man (offensive, outdated)

Big girl’s blouse Weak, wimpy man (offensive, gendered)

Pansy Weak person (offensive, homophobic implications)

Nancy/Nancy boy Effeminate man (very offensive, homophobic)

Ponce Effeminate man or someone who lives off others

Tight Stingy, unwilling to spend money “Tight-fisted”

Tight-arse Very stingy person

Skinflint Extremely miserly person

Mean Stingy (British usage differs from American)

Miser Someone who hoards money

Cheapskate Stingy person

Scrooge Miser (from Dickens character)

Greedy guts Greedy person, especially about food

Selfish git Self-centered person

Egotist Self-absorbed person

Up themselves Arrogant, full of themselves “He’s so far up himself”

Full of themselves Arrogant, conceited

Stuck-up Snobbish, thinking oneself superior

Snob Someone who looks down on others

Toff Upper-class person (can be neutral or insulting depending on context)

Posh twat Wealthy person, used insultingly

Pompous Self-important, pretentious

Pretentious Trying to appear more important or cultured than one is

Poser Someone who pretends to be something they’re not

Try-hard Someone who tries too hard to fit in or be cool

Show-off Someone who constantly seeks attention

Attention seeker Someone desperate for attention

Drama queen Someone who overreacts to everything

Windbag Someone who talks too much without saying anything meaningful

Blowhard Boastful person who talks too much

Bighead Arrogant person

Big-headed Conceited, arrogant

Swollen-headed Excessively proud

Work and Competence Insults

Useless Incompetent, worthless “Absolutely useless”

Waste of space Completely useless person

Dead weight Burden, useless person

Lazy sod Lazy person

Idle Lazy, not working

Workshy Avoiding work

Skiver Someone who avoids work or responsibility

Slacker Lazy, unproductive person

Layabout Lazy person who does nothing

Dosser Lazy person, homeless person

Bum Lazy person (different from American “homeless person”)

Good-for-nothing Worthless, useless person

Deadbeat Irresponsible person, especially regarding finances

Sponger Someone who lives off others

Scrounger Someone who gets things without paying

Freeloader Someone who takes advantage of others’ generosity

Parasite Person who lives off others

Leech Person who drains resources from others

Hanger-on Person who associates with others for benefit

Social Behavior Insults

Cheeky Impertinent, disrespectful (can be playful) “Cheeky git” or “Cheeky bastard”

Mouthy Talks back, disrespectful

Lippy Disrespectful, talking back

Cocky Overconfident, arrogant

Brash Loud, aggressive, lacking subtlety

Obnoxious Extremely unpleasant, annoying

Oik Obnoxious, uncultured person

Yob Rowdy, antisocial young man

Yobbo Loutish, badly behaved person

Lout Rough, aggressive person

Hooligan Violent, destructive person

Thug Violent criminal

Ned Scottish equivalent of chav, antisocial youth

Scally Liverpool equivalent of chav

Pikey Offensive term for travellers or working-class people

Ruffian Violent, lawless person

Scoundrel Dishonest, unscrupulous person

Rogue Dishonest person (can be affectionate: “lovable rogue”)

Villain Criminal, bad person

Wrong’un Bad person, someone who’s “wrong”

Bad egg Untrustworthy or immoral person

Dodgy character Suspicious, untrustworthy person

Creep Unpleasant person, often with sexual connotations

Perv/Pervert Sexual deviant, creepy person

Dirty old man Older man with inappropriate sexual interest

Lech Someone who makes unwanted sexual advances

Sleazebag Morally repugnant person

Slimeball Repulsive, unethical person

Drinking and Partying Insults

Pisshead Heavy drinker, alcoholic

Alkie/Alky Alcoholic

Wino Alcoholic, especially someone who drinks cheap wine

Lush Heavy drinker (older term)

Soak Heavy drinker

Boozer Heavy drinker or pub

Drunkard Alcoholic

Sot Habitual drunkard (old-fashioned)

Lightweight Someone who can’t handle alcohol “What a lightweight”

Can’t handle their drink Gets drunk easily

Age and Generation Insults

Old codger Old man (slightly affectionate or insulting)

Old git Grumpy old person

Old bag Old woman (very offensive)

Old bat Unpleasant old woman

Old biddy Gossipy old woman

Old fart Old person, especially boring or conservative one

Fossil Very old person

Old fogey Old-fashioned, conservative old person

Geezer Old man (can be neutral or insulting depending on context)

Coffin dodger Very old person (dark humor)

Past it Too old, no longer capable

Over the hill Too old

Decrepit Old and feeble

Sprog Child (can be affectionate or dismissive)

Brat Badly behaved child

Little shit Badly behaved child or young person

Ankle biter Small child

Rug rat Small child

Kid/Kiddo Can be patronizing when used to adults

Whippersnapper Young, inexperienced person who’s impudent

Young pup Inexperienced young person

Regional Variations and Specialties

Scottish Insults

Bawbag Scrotum, used as insult (contemptible person)

Numpty Idiot, fool (now used throughout Britain)

Eejit Idiot (also Irish)

Bampot Idiot, crazy person

Fanny Idiot (different from English usage where it means vagina)

Tube Idiot

Walloper Idiot, contemptible person

Dobber Penis, or idiot

Weapon Idiot, tool

Roaster Idiot, embarrassing person

Rocket Idiot

Clown Idiot, fool

Dafty Silly person

Ned Antisocial youth, Scottish chav

Radge Crazy person or angry person

Pure mental Completely crazy (Scottish intensifier)

Northern English Insults

Mardy Moody, sulky (East Midlands/Yorkshire) “Mardy arse”

Nesh Weak, unable to handle cold (Midlands)

Soft lad Weak person (Northern)

Daft apeth Silly person (Northern, from “halfpenny”)

Mard arse Sulky, moody person (Northern)

Wazzock Stupid person (Yorkshire)

Divvy Idiot (Liverpool)

Scally Antisocial youth (Liverpool)

Our kid Can be patronizing when not actually addressing sibling (Northern)

Nowt-headed Empty-headed, stupid (Northern)

Barmpot Foolish person (Northern)

London/Cockney Insults

Mug Fool, someone easily taken advantage of “You mug”

Melt Weak, pathetic person (modern London slang)

Wet wipe Weak person (modern London)

Waste man/Wasteman Useless person (London urban slang)

Neek Nerd or weak person (London)

Donut Idiot (London)

Muppet Fool (popularized in London)

Plonker Idiot (Cockney, from “Only Fools and Horses”)

Berk Fool (from Cockney rhyming slang)

Merchant Added to other words for emphasis: “Flash merchant” (show-off)

Welsh Insults

Twp Stupid (Welsh word used in English)

Cwtch Not an insult, but opposite—means cuddle/hug

Cont Welsh pronunciation affecting the worst British insult

Daft Common throughout Wales

Irish-Influenced British Insults

Gobshite Person who talks nonsense

Eejit Idiot

Thick Stupid (very common in Ireland and Britain)

Amadán Fool (Irish word sometimes used)

Gombeen Corrupt person

Hallion Good-for-nothing person

Bollix Irish spelling/pronunciation of bollocks

Class-Based Insults

British culture’s class consciousness produces unique insults:

Working Class → Middle/Upper Class

Posh twat Wealthy, privileged person

Toff Upper-class person

Stuck-up Snobbish

Hoity-toity Acting superior

Coffee-nosed Snobbish

Silver spoon Born into wealth (short for “born with silver spoon in mouth”)

Trust fund baby Someone living off inherited wealth

Fancy pants Someone who thinks they’re better

Too good for the likes of us Acting superior

Thinks their shit doesn’t stink Acting superior

Middle/Upper Class → Working Class

Chav Working-class person with particular style markers (very offensive)

Pikey Extremely offensive term for travellers or working-class

Common Lacking refinement or class

Rough Low-class, unrefined

Uncouth Lacking manners or refinement

Coarse Lacking refinement

Vulgar Tasteless, lacking refinement

Unrefined Lacking sophistication

Low Base, lacking class

Oik Obnoxious, uncultured person

Yob/Yobbo Loutish working-class youth

Ned/Scally/Kev Regional variations on chavs

Modern British Insults (Social Media Age)

Wasteman/Wastewoman Useless, disappointing person (urban slang)

Wet wipe Weak, pathetic person

Melt Pathetic, weak person

Wallad Idiot (London)

Neek Cross between nerd and geek, means weak person

Div Idiot (originally from “divvy”)

Muppet Still going strong

Basic Unoriginal, mainstream (adopted from American)

Karen Entitled middle-aged woman (adopted from American)

Boomer Dismissive term for older person out of touch

Gammon Middle-aged, red-faced, angry conservative (political insult)

Snowflake Overly sensitive person

Nonce Pedophile or child molester (extremely serious accusation)

Paedo Pedophile (extremely serious)

Bellend Still popular, means idiot

Absolute weapon Complete idiot (Scottish spreading to England)

Clown Idiot, fool (increasingly popular)

Joke Someone not to be taken seriously “He’s a joke”

Wastage Wasted potential, disappointing person

Intensifiers and Modifiers

British insults can be amplified or modified:

Intensifiers (Making It Worse)

Absolute “You absolute wanker” (much worse than just “wanker”)

Complete “Complete tosser”

Total “Total dickhead”

Right “Right idiot” or “Proper idiot”

Proper “Proper twat”

Utter “Utter bellend”

Pure “Pure mental” (Scottish)

Massive “Massive prick”

Giant “Giant cock”

Enormous “Enormous wanker”

Modifiers (Adding Flavor)

Little Can be patronizing: “Little shit”

Old “You old git”

Miserable “Miserable git”

Cheeky Can soften or emphasize: “Cheeky bastard”

Stupid “Stupid prick”

Lazy “Lazy git”

Fat “Fat bastard” (very offensive)

Ugly “Ugly minger”

Useless “Useless tosser”

Pathetic “Pathetic wanker”

Phrases and Combinations

Creative British Insult Phrases

“Not the sharpest knife in the drawer” Not intelligent

“Couldn’t pour water out of a boot with instructions on the heel” Very stupid

“Couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery” Completely incompetent

“All fur coat and no knickers” All show, no substance

“As useful as a chocolate teapot” Completely useless

“As useful as a screen door on a submarine” Useless

“About as much use as a one-legged man in an arse-kicking contest” Useless

“Thick as two short planks” Very stupid

“Thick as mince” Extremely stupid (Scottish)

“Daft as a brush” Very silly

“Mad as a box of frogs” Crazy

“Away with the fairies” Not paying attention, mentally absent

“Few sandwiches short of a picnic” Not very intelligent

“Not playing with a full deck” Missing something mentally

“Lights are on but nobody’s home” Appears functional but lacks intelligence

“Elevator doesn’t go all the way to the top” Not fully intelligent

“Sharp as a marble” Not sharp at all, stupid

“Bright as a broken bulb” Not bright, stupid

“Lost the plot” Gone crazy

“Gone round the bend” Crazy

“Completely barking” Crazy

“Nutty as a fruitcake” Crazy

“More front than Brighton” Extremely bold or cheeky (Brighton has a famous seafront)

“Face like a bulldog chewing a wasp” Ugly or angry expression

“Face like a smacked arse” Miserable, unpleasant expression

“Face for radio” Ugly (implying they should be heard, not seen)

“Butter wouldn’t melt in their mouth” Acting innocent while being cunning (sarcastic)

“Think the sun shines out of their arse” Arrogant, self-important

“Head up their own arse” Self-absorbed, arrogant

“So far up themselves they can see their tonsils” Extremely arrogant

“Couldn’t give a monkey’s” Doesn’t care at all (from “couldn’t give a monkey’s fuck”)

“Couldn’t care less” Doesn’t care (note: British say “couldn’t,” Americans often incorrectly say “could”)

“Get stuffed” Expression of rejection

“Go boil your head” Go away, expression of dismissal

“Sod off” Go away

“Piss off” Go away (ruder)

“Bugger off” Go away

“On your bike” Go away

“Jog on” Go away, leave

“Do one” Go away, leave (modern)

“Sling your hook” Go away

“Naff off” Go away (deliberately mild version)

Context Is Everything: When Insults Aren’t Really Insults

Understanding when British insults are friendly requires cultural knowledge:

Friendly Contexts

Between Close Friends:

- “You absolute wanker!” (hearing about friend’s good fortune)

- “You lucky bastard!” (congratulating friend)

- “You cheeky sod!” (playful response to teasing)

- “You pillock!” (friend did something silly)

With Family:

- “Don’t be daft” (dismissing worry)

- “You silly sod” (affectionate)

- “Soft lad” (Northern, affectionate)

Banter:

- British culture revolves around “taking the piss” (mocking playfully)

- Friends insult each other constantly

- Refusing to join in seems standoffish

- The closer the friendship, the harsher the insults can be

Genuinely Offensive Contexts

To Strangers: Almost any insult to a stranger is genuinely offensive, not banter.

Wrong Tone: Same words with anger, contempt, or genuine malice are insults, not banter.

Power Imbalances: Boss to employee, adult to child—insults aren’t friendly.

First Meetings: Don’t use insults with new acquaintances—wait for established rapport.

When Someone Says “That’s Not On”: If someone objects, it’s not banter—it’s offensive.

British vs. American Insult Differences

Words That Are Worse in Britain

Cunt: More offensive in Britain than Australia, but used more casually than in America where it’s considered one of the absolute worst words

Wanker: Common in Britain, would be shocking in America

Twat: Very common in Britain, more shocking in America

Words That Are Worse in America

Bastard: Much more casual in Britain (can be friendly: “lucky bastard”)

Bugger: Mild in Britain, stronger in America

Bloody: Once very offensive in Britain, now quite mild; Americans barely register it

Cultural Differences

British:

- More comfortable with swearing

- Insults often affectionate

- Elaborate, creative insults valued

- Indirect insults (“How interesting”)

- Class-based insults common

American:

- More direct communication

- Insults usually mean insults

- Religious/moral insults more common

- Racial insults taken very seriously

- Class supposedly doesn’t exist (but does)

When Insults Cross the Line

Even in Britain’s insult-friendly culture, some things are beyond the pale:

Always Offensive

Racist Language: Any racial slurs are completely unacceptable and illegal under hate speech laws.

Homophobic Slurs: Words like “poof,” “faggot,” “queer” (when used as insult) are hate speech.

Sexist Insults: While some gendered insults persist, increasing awareness makes them less acceptable.

Disability-Related Insults: “Retard,” “spaz,” “mong” are highly offensive.

Religious Insults: Insulting someone’s religion is considered extremely poor form.

Appearance-Based (Usually): Insulting weight, disabilities, disfigurements is generally beyond acceptable.

Context-Dependent

Slag/Slapper/Slut: These gendered insults are increasingly recognized as unacceptable.

Chav/Pikey: Class-based insults now challenged as classist and offensive.

Fat/Ugly: Appearance insults increasingly seen as bullying.

Mental/Psycho: Mental health insults increasingly problematic.

How to Respond to British Insults

If It’s Friendly Banter

Return Fire: Insult them back (approximately equal severity)

Acknowledge: “Fair point” or “You’re not wrong”

Exaggerate: “Guilty as charged” or “I wear that badge with pride”

Self-Deprecate: “Coming from you, I’ll take that as a compliment”

If It’s Actually Offensive

Call It Out: “That’s not on” or “That’s bang out of order”

Set Boundaries: “I don’t appreciate that” (very serious in British culture)

Walk Away: “I’m not having this conversation”

Report (Serious Cases): Racist, sexist, homophobic insults can be hate crimes in Britain

Regional Insult Spotting: A Guide

If you hear:

- “Bawbag,” “numpty,” “pure mental” → Scotland

- “Mardy,” “wazzock,” “soft lad” → Northern England

- “Divvy,” “scally” → Liverpool

- “Melt,” “wet wipe,” “wasteman” → London

- “Chav” → England (especially South)

- “Ned” → Scotland

- “Gobshite,” “eejit” → Ireland/Northern Ireland

- “Twp” → Wales

Compound Insults: British Creativity at Its Finest

British speakers excel at combining words to create more elaborate insults:

Two-Word Combinations

Absolute + Noun:

- Absolute wanker

- Absolute tosser

- Absolute tool

- Absolute muppet

- Absolute bellend

- Absolute weapon (Scottish)

- Absolute clown

- Absolute joke The word “absolute” intensifies any insult significantly.

Complete + Noun:

- Complete prick

- Complete dickhead

- Complete knobhead

- Complete arsehole

- Complete melt Similar intensifying effect to “absolute”

Total + Noun:

- Total tosspot

- Total waste of space

- Total gobshite

- Total numpty

Right + Noun: Very British intensifier:

- Right git

- Right bastard

- Right muppet

- Right numpty

- Right plonker Often implies the person is a thorough or exemplary version of the insult

Proper + Noun:

- Proper twat

- Proper wanker

- Proper dickhead Working-class intensifier, especially Northern/Midlands

Cheeky + Noun: Can soften or emphasize depending on tone:

- Cheeky bastard

- Cheeky git

- Cheeky sod

- Cheeky bugger

- Cheeky cow Often used with affection or playful annoyance

Silly + Noun: Generally affectionate:

- Silly sod

- Silly git

- Silly muppet

- Silly bugger

- Silly cow Usually mild, often said with fondness

Stupid + Noun: Emphasizes foolishness:

- Stupid prick

- Stupid git

- Stupid bastard

- Stupid sod More insulting than “silly”

Lazy + Noun: Targets work ethic:

- Lazy git

- Lazy sod

- Lazy bastard

- Lazy bugger

- Lazy arse

Miserable + Noun: Targets personality:

- Miserable git

- Miserable sod

- Miserable bastard

- Miserable cow

- Miserable old git

Little + Noun: Often patronizing:

- Little shit

- Little sod

- Little git

- Little bastard

- Little tosser Can be condescending regardless of actual size

Old + Noun: Age-related, often affectionate:

- Old git

- Old sod

- Old bastard

- Old bugger

- Old fart Can be friendly between people of similar age

Three-Word Combinations

Adjective + Adjective + Noun:

- Stupid lazy git

- Miserable old bastard

- Cheeky little sod

- Useless bloody idiot

- Silly old fool

Adjective + [Expletive] + Noun:

- Absolute fucking wanker (very strong)

- Complete bloody idiot

- Total fucking muppet

- Right bloody nuisance

Body Part Insults

Face-Related:

- Frog-face

- Pizza-face (acne)

- Horse-face

- Rat-face

- Moon-face (round face)

- Butter-face (everything but her face)

Head-Related:

- Blockhead (stupid)

- Fathead (stupid)

- Bonehead (stupid)

- Meathead (stupid, muscle-bound)

- Airhead (stupid)

- Pinhead (stupid, small-minded)

- Egghead (intellectual, can be insulting or neutral)

- Dickhead (general insult)

- Knobhead (general insult)

Size-Related:

- Lardarse (overweight)

- Fat bastard (very offensive)

- Porker (overweight)

- Tub of lard (overweight)

- Stick insect (very thin)

- Beanpole (very tall and thin)

- Short-arse (short person)

- Midget (very offensive)

- Shrimp (small person)

Profession and Occupation Insults

British culture has insults related to various professions and social roles:

Tradesperson Insults

Cowboy: Incompetent tradesperson or business “Cowboy builder” – shoddy workmanship “Bunch of cowboys” – unprofessional outfit

Bodger: Someone who does shoddy work “Bodge job” – poorly done work

Chancer: Someone who takes risks or tries to get away with things

Spiv: Flashy, untrustworthy businessman or black marketeer (dated but still used)

Shark: Unscrupulous businessperson “Loan shark,” “pool shark”

Con artist: Swindler, fraudster

Wide boy: Untrustworthy wheeler-dealer

Del Boy: Like Arthur Daley, references “Only Fools and Horses” character—dodgy dealer

Arthur Daley: Shifty businessman (from TV series “Minder”)

Authority Figure Insuits

Jobsworth: Petty official who enforces rules rigidly Origin: “It’s more than my job’s worth”

Busybody: Interfering person

Clipboard warrior: Petty bureaucrat

Pen pusher: Boring office worker

Suit: Corporate type, out of touch person

Bean counter: Accountant (dismissive)

Box ticker: Someone who just goes through motions

Yes man: Sycophant who agrees with authority

Arse licker: Sycophant (vulgar)

Brown-noser: Sycophant

Toady: Sycophant

Crawler: Sycophant

Creep: Sycophant (among other meanings)

Teachers pet: Student who curries favor

Suck-up: Person who ingratiates themselves

Service Industry Insults

Jobsworth: Unhelpful service worker who hides behind rules

Jobs worth: Same as above

Rude boy/girl: Disrespectful service worker

Couldn’t care less: Apathetic worker

Couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery: Incompetent organizer/manager

Media and Entertainment

Hack: Poor journalist or writer

Tabloid journalist: Low-quality sensationalist journalist

Talking head: TV pundit with no real expertise

Z-lister: Very minor celebrity

Has-been: Former celebrity now irrelevant

Never-was: Person who never achieved fame despite attempts

One-hit wonder: Person known for one thing only

Flash in the pan: Brief success followed by obscurity

Sell-out: Person who compromised principles for money

Situation-Specific British Insults

Driving-Related

Sunday driver: Slow, overly cautious driver

Boy racer: Young man driving recklessly

White van man: Aggressive tradesperson driver (stereotype)

Middle-lane hogger: Driver who stays in middle lane on motorway

Road hog: Selfish driver

Backseat driver: Passenger who criticizes driving

Tailgater: Driver who follows too closely

Slowcoach: Very slow person (not just driving)

Queue-Related (Very Important in Britain!)

Queue jumper: Person who doesn’t wait their turn (very serious in Britain!)

Pushy: Someone who doesn’t respect queues

No manners: General complaint about queue-jumper

Barge in: To push into queue rudely

Think they own the place: Someone acting entitled in queue

Pub and Social Situations

Lightweight: Can’t handle alcohol

Sloppy drunk: Drunk and messy

Pisshead: Heavy drinker

Getting lairy: Becoming aggressive when drunk

Mouthy when drunk: Talks too much/aggressively when drinking

Sponger: Person who never buys rounds

Tight git: Won’t buy drinks

Round dodger: Avoids buying rounds

Sneak: Person who leaves before their round

Bogart: Hogging something (often a joint)

Greedy guts: Eating/drinking too much

Football (Soccer) Related

Armchair supporter: Supporter who never attends matches

Glory hunter: Supports successful team only

Plastic fan: Fake, uncommitted supporter

Hooligan: Violent football fan

Yob: Rowdy, antisocial fan

Mug: Gullible supporter

Bottler: Coward, team that loses under pressure

Diving: Player who fakes fouls (not exactly insult but critical)

Dating and Relationships

Player: Person who dates multiple people deceptively

Love rat: Cheater (tabloid favorite)

Two-timer: Person conducting two relationships

Slag: Promiscuous person (usually woman, derogatory)

Slapper: Promiscuous woman (derogatory)

Dog: Unattractive person

Butterface: Body good, face bad

Swamp donkey: Very unattractive person (harsh)

Five-pinter: Person who looks attractive only after drinking five pints

Moose: Unattractive person

Munter: Unattractive person

Stage five clinger: Overly attached person

Bunny boiler: Dangerously obsessive person (from “Fatal Attraction”)

Psycho: Crazy romantic partner

Control freak: Domineering partner

Gold digger: Person interested only in money

Trophy wife/husband: Attractive spouse chosen for looks

Toy boy: Younger male partner (patronizing)

Cradle snatcher: Person dating someone much younger

Old enough to be their father/mother: Age-inappropriate relationship comment

Work-Related Situations

Clock watcher: Someone who does minimum work

Shirker: Work avoider

Skiver: Someone who avoids work

Slacker: Lazy worker

Time waster: Unproductive person

Dead weight: Useless team member

Passenger: Person not contributing

Yes man: Agrees with everything boss says

Brown-noser: Sucks up to boss

Backstabber: Betrays colleagues

Gossip: Spreads rumors

Stirrer: Creates trouble

Pot stirrer: Causes problems

Troublemaker: Creates difficulties

Loose cannon: Unpredictable, risky person

Maverick: Non-conformist (can be positive or negative)

One-man band: Won’t delegate or work with team

Control freak: Micromanager

Dragon: Fierce, unpleasant manager (often woman, sexist)

Slave driver: Demanding manager

Tyrant: Oppressive manager

Age-Appropriate Insults: What Kids Say

British children and teenagers use somewhat different insults:

Primary School Age

Meanie: Mean person

Meanie-head: Mean person (child-friendly)

Poo-poo head: Childish insult

Wee-wee head: Childish insult

Stupid-head: Basic insult

Dummy: Stupid person

Baby: Immature person

Cry-baby: Someone who cries easily

Tattletale/Telltale: Informer

Snitch: Informer

Grass: Informer (British specific)

Teacher’s pet: Student who curries favor

Swot: Student who studies too much

Nerd: Socially awkward smart student

Geek: Similar to nerd

Dweeb: Awkward person

Dork: Foolish person

Loser: Unsuccessful person

Lame: Uncool

Saddo: Pathetic person

Billy no-mates: Person with no friends

Smelly: Unhygienic person

Teenage Insults

Neek: Nerd/geek combination (London)

Wasteman: Useless person (urban)

Wet wipe: Weak person (modern)

Melt: Pathetic person

Basic: Unoriginal person

Tryhard: Someone trying too hard

Cringe: Embarrassing person

Extra: Over-the-top person

Salty: Bitter, upset person

Pressed: Upset, bothered

Shook: Upset, rattled

Salty: Bitter about something

Butthurt: Overly sensitive

Triggered: Easily offended (often used mockingly)

Snowflake: Overly sensitive person

Karen: Entitled middle-aged woman (from American)

Kevin: British male equivalent of Karen

Boomer: Older person out of touch

Fossil: Very old person

Dinosaur: Outdated person

Relic: Old-fashioned person

Historical and Literary British Insults

Some insults have fascinating histories:

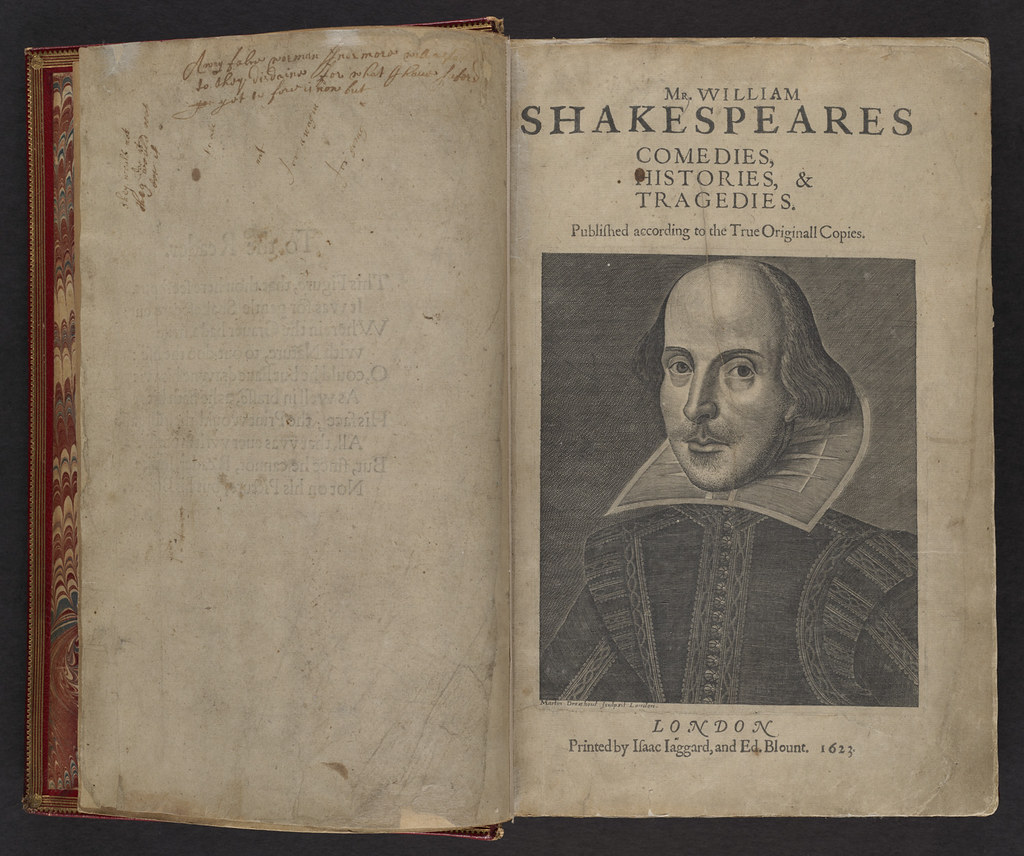

Shakespeare-Era Insults Still in Use

Villain: From Shakespeare, means evil person

Scoundrel: Dishonest person (old-fashioned)

Rogue: Dishonest person (can be affectionate: “lovable rogue”)

Knave: Dishonest man (archaic but understood)

Cur: Contemptible person (literally mongrel dog)

Blackguard: Scoundrel (pronounced “blaggard”)

Rascal: Mischievous person (often affectionate now)

Rapscallion: Mischievous person (playful)

Scalawag: Rascal (American but used in Britain)

Ne’er-do-well: Worthless person

Good-for-nothing: Worthless person

Wastrel: Wasteful, worthless person

Victorian-Era Insults

Bounder: Untrustworthy man

Cad: Man who behaves dishonorably

Scallywag: Rascal

Hooligan: Rowdy troublemaker

Rapscallion: Rogue

Vagabond: Wandering criminal

Ruffian: Violent person

Charlatan: Fraud, faker

Mountebank: Fraud, faker

Quack: Fake doctor or expert

Humbug: Fraud, nonsense

Poppycock: Nonsense

Balderdash: Nonsense

Codswallop: Nonsense

Rot: Nonsense

Tosh: Nonsense

Rubbish: Nonsense (still very common)

Piffle: Nonsense

Twaddle: Nonsense

Drivel: Nonsense

Claptrap: Nonsense

Dickens-Influenced Insults

Scrooge: Miser

Gradgrind: Harsh, facts-obsessed person

Uriah Heep: Insincere, sycophantic person

Dodger: Sly, evasive person (from Artful Dodger)

Fagin: Corrupter of youth

British Insults in Literature and Film

Popular culture has contributed many insults to British vocabulary:

From “Monty Python”

Your mother was a hamster and your father smelt of elderberries: Elaborate nonsensical insult

Silly English knights: General dismissive phrase

Go and boil your bottoms: Dismissive phrase

From “Blackadder”

The show was a masterclass in elaborate British insults:

- “The eyes are open, the mouth moves, but Mr. Brain has long since departed”

- “As thick as a whale omelette”

- “As cunning as a fox who’s just been appointed Professor of Cunning”

From “Only Fools and Horses”

Plonker: Made famous by Del Boy calling Rodney this

Dipstick: Fool

Wally: Idiot

42nd cousin of some pleasant peasant: Elaborate put-down

From “The Thick of It” and “In The Loop”

Malcolm Tucker’s elaborate creative swearing:

- “Omnishambles” (complete disaster)

- Various combinations of profanity with incredible creativity

From “Harry Potter”

Mudblood: Slur for non-pure-blood wizards (fictional but understood)

Squib: Non-magical person from magical family

From British Rap/Grime

Wasteman: Useless person

Neek: Weak person

Wet: Weak, pathetic

Snake: Betrayer

Moving mad: Acting crazy

Gassed: Overly confident

Teefing: Stealing

Muggy: Disrespectful

The Future of British Insults

British insults continue to evolve:

Americanization

American terms increasingly adopted by British youth:

- Basic

- Karen

- Simp

- Salty

- Shade (throwing shade)

- Drag (dragging someone)

Social Media Influence

Online culture creating new insults:

- Troll

- Keyboard warrior

- Snowflake

- Boomer

- Stan (obsessive fan, can be insulting)

- Cringe

- Sus (suspicious)

Reclaimed Insults

Some insults being reclaimed by communities:

- Queer (by LGBTQ+ community)

- Bitch (by some women)

- Nerd/geek (now often positive)

Declining Use

Some insults fading due to changing attitudes:

- Terms with homophobic connotations

- Overtly sexist terms

- Disability-related slurs

- Racist language (rightly criminalized)

Conclusion: The Art of British Insults

British insults represent more than mere profanity—they’re a sophisticated social tool for establishing relationships, expressing affection, releasing frustration, and navigating the complexities of British class and regional identity.

Understanding British insults requires grasping several key principles:

- Context matters more than words: The same phrase can be devastating or endearing depending on who says it, how, and to whom.

- Friendship enables harsher language: The closer the relationship, the more severe the acceptable insults.

- Class consciousness persists: Many insults reference social status in ways Americans might not recognize.

- Regional variation is significant: What’s common in Scotland might be unknown in London.

- Evolution continues: Modern British insults incorporate social media language while maintaining traditional favorites.

- When in doubt, err on the side of caution: Wait for established rapport before deploying insults, and watch how native speakers navigate their use.

For foreigners in Britain, the safest approach is to listen and learn before participating. Observe how British people insult each other, note the contexts, and gradually develop your sense of what’s acceptable. Pay attention to relationships, tones, and reactions. When you do join in, start mild and increase severity only as relationships deepen and you better understand the boundaries.

Remember: in Britain, being called a “wanker” by a close friend is a sign of affection. Being told you’re “quite interesting” by a new acquaintance might be the worst insult you receive all day. That’s the beauty and complexity of British insult culture—it rewards subtlety, irony, and social awareness while punishing those who can’t distinguish friendly banter from genuine hostility.

Master British insults, and you’ll have mastered a crucial element of British social interaction. Just don’t call someone a cunt unless you really, really mean it—or unless you’re Australian and everyone’s already drunk.